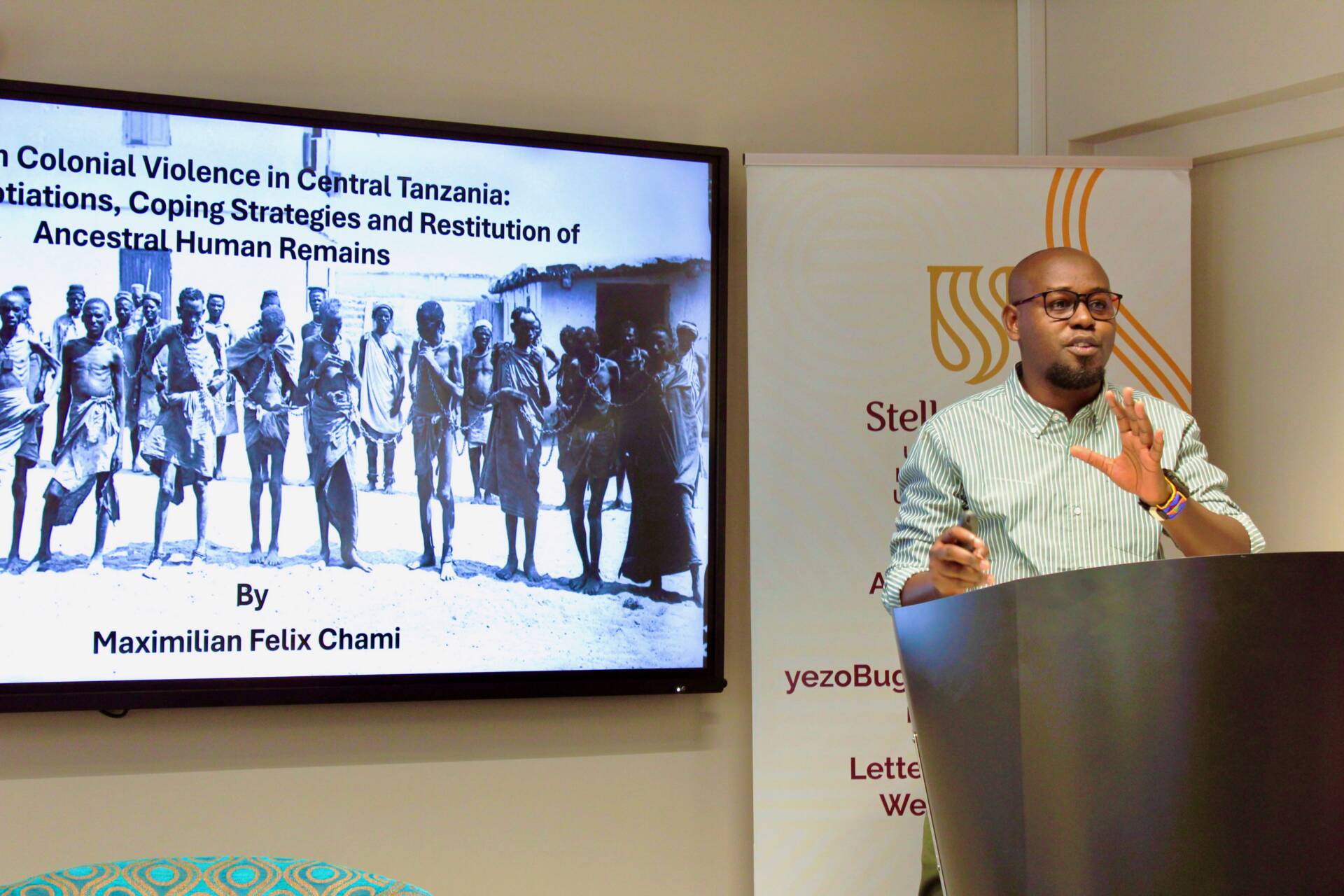

The seminar German Colonial Violence in Central Tanzania: Engaging the Afterlives of History formed part of AVReQ’s Bearing Witness series, interrogating practices of memory, museology, and the ethics of bearing witness. Facilitated by Dr Sophia Sanan, the discussion examined how violent colonial pasts are remembered, how museums respond to calls for restitution, and how communities negotiate histories of trauma across generations. The seminar featured Dr Maximillian Chami, a cultural heritage specialist, whose research explores heritage restitution, particularly the repatriation of human remains from German institutions.

In her introduction, Dr Sanan framed the seminar as part of a broader inquiry into “how we bring historical events into conversation with the present, how we negotiate what should be remembered and how, and what we are able to repair.” She emphasised the profound challenges facing museums, whose authority has been questioned by decolonial, indigenous, and feminist critiques. At the centre of this conversation was the question of human remains collected during colonial rule, and what their restitution signifies for both communities of origin and global institutions.

Dr Chami began by offering historical context. Before the Berlin Conference, the region that became German East Africa was organised around chieftaincies and diverse ethnic communities. German colonial rule disrupted these structures and unleashed violence, followed later by British control until independence in 1961.

Archival research in Göttingen revealed that between 1910 and 1912, seventy-one human remains were taken from central Tanzania with support from the colonial government and the Hamburg Geographische Gesellschaft (Geographical Society). These belonged to eleven ethnic groups, though Dr Chami focused on the Isanzu and Nyaturu. Oral histories from these communities recall the deaths of Chief Kitentemi of the Isanzu and Chief Kidanka of the Nyaturu. Both were executed by German forces, their remains removed and later transferred to Europe. Community memory continues to connect these killings to drought, famine, and cultural dislocation. As Dr Chami explained, “taking for them the skull…carries a lot of things, the knowledge, everything.”

The discussion highlighted the complexities of restitution in Tanzania. Following independence, state policy prioritised national cohesion, with President Julius Nyerere abolishing the chieftaincy system in 1963. This made open discussion of ethnic identity politically sensitive, as leaders sought to avoid the risks of interethnic conflict seen elsewhere on the continent. Dr Chami noted that identity issues were handled “very carefully” during this period. Despite this, local communities have sustained memory practices through commemorations, memorial sites, and state-recognised initiatives, such as the renaming of a stadium in Chief Kidanka’s honour. These practices underscore the resilience of cultural memory in the face of broader narratives that emphasised national unity over ethnic identity.

Dr Sanan highlighted how Dr Chami’s research brought together oral histories, archival materials in German, and photographs of colonial executions. While these photographs corroborated oral accounts, Dr Chami explained that showing them to communities risked retraumatisation. At the same time, their presence in European archives raised ethical questions about ownership, display, and institutional accountability.

A central theme of the discussion was the importance of dialogue in restitution. Dr Chami argued that restitution should not be reduced to financial compensation or administrative repatriation, but must involve communities directly, acknowledging their spiritual and cultural needs. He pointed to comparative examples, such as Māori communities in New Zealand, where dialogue and preparation were integral to the repatriation of ancestral remains. He observed that “the community still have not yet got this chance to sit down, to discuss this colonial legacy.”

The conversation concluded with reflections on the role of museums. Participants noted the strikingly small space devoted to colonial history in Tanzania’s National Museum, compared with exhibits such as presidential cars and aeroplanes. Dr Chami explained that these curatorial decisions reflect broader narratives about history and identity, raising “very difficult questions about the future of museums as they have been, and kind of suggesting that they will not look the same for very long.” Thus, what emerged clearly from the seminar is that restitution is not simply about returning objects or remains. It is about recognising the cultural and spiritual significance of ancestors, confronting unresolved histories of violence, and creating new spaces, both physical and dialogical, where communities can articulate what healing and justice mean for them. The afterlives of colonial violence, as this discussion made evident, continue to shape the present in profound ways.