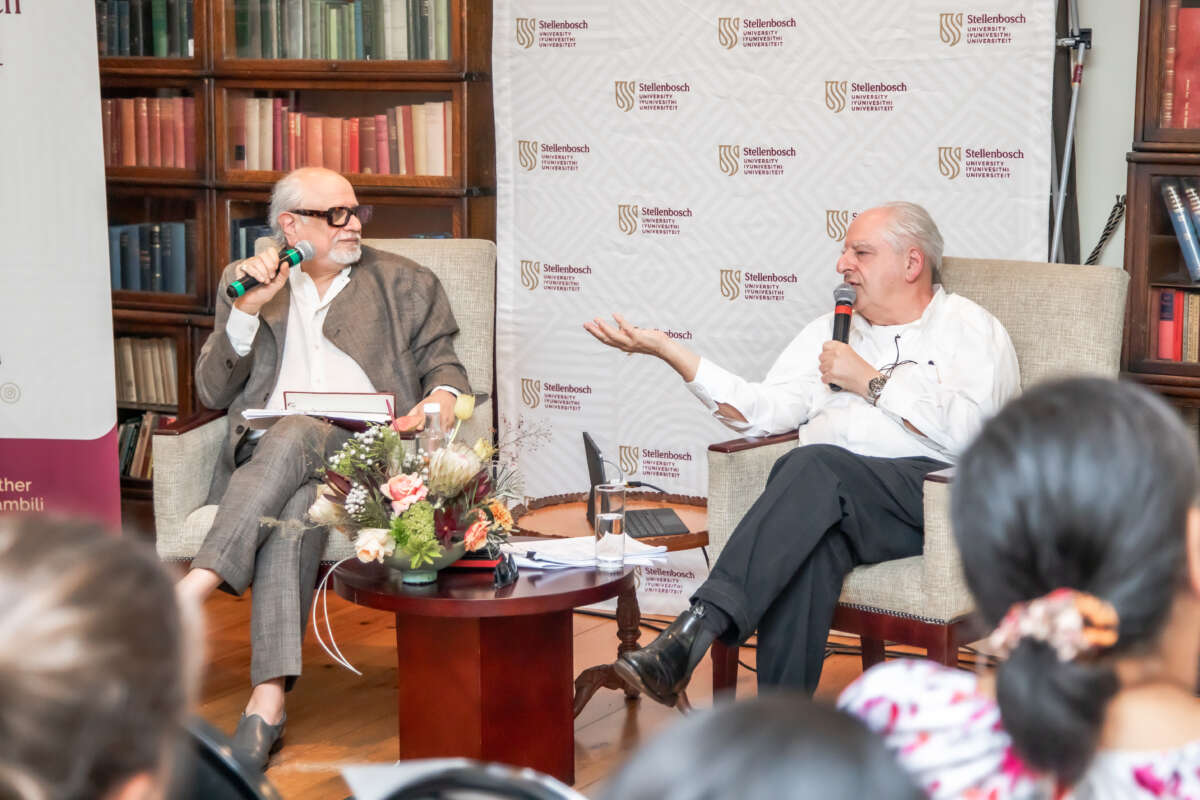

Two phenomenal minds dazzled a Stellenbosch audience recently when they spent 90 minutes in awe of the intellectual and creative gymnastics of the renowned scholar Prof Homi Bhabha and the acclaimed artist William Kentridge.

Entitled “The Surrealism of Fanon: Montage and Social Dialogue,” the event, held on 14 March 2024, was organised by the Centre for the Study of the Afterlife of Violence and the Reparative Quest (AVReQ) at Stellenbosch University (SU).

Bhabha is the Anne F. Rothenberg Professor of the Humanities in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at Harvard University. He has received numerous awards and honorary professorships, including being an Extraordinary Professor affiliated with AVReQ.

Kentridge is considered one of South Africa’s most important artists and is known for his work across various mediums, including drawings, films, theatre and operas. He has directed theatre productions for prestigious institutions globally and has received honorary doctorates from several universities, including Yale, Columbia and the University of London. He has been awarded the Kyoto Prize (2010), the Princesa de Asturias Award (2017) and the Praemium Imperiale Prize (2019).

Kentridge often works with dozens of collaborators, including artists, performers, and musicians, to make art that is grounded in history, literature, politics and science.

The discussion at STIAS was introduced by AVReQ Director Prof Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela and centred on Kentridge’s new project, a chamber opera called The Great YES, The Great No which is set on an imaginary 1941 sea voyage from Marseille in France to the Caribbean island Martinique.

The opera, which will premiere in July this year in France, features a diverse cast of historical figures, including André Breton, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Victor Serge and Anna Seghers and fictionalises the journey by adding characters like Aimé and Suzanne Césaire, the Nardal sisters, Frantz Fanon, Josephine Bonaparte, Josephine Baker, Leon Trotsky, Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and Joseph Stalin.

The conversation between Bhabha and Kentridge touched on themes of surrealism, montage, fragmentation and social dialogue, against the backdrop of the artistic process informing The Great YES, The Great No.

Fragmented creativity

Both speakers have been influenced by surrealism. Bhabha has written about the surrealist aspects of Fanon’s work and his research has contributed to the ongoing discourse on postcolonial theory and the role of art and literature in addressing issues of colonialism and its aftermath. His introduction to Fanon’s work has provided a critical perspective on the philosopher’s ideas and its relevance to contemporary issues, such as migration and the cultural reimagining of historical injustices.

Bhabha asked Kentridge about the inspiration he finds in historical moments to interrogate universal issues and how surrealism informs his art.

In explaining the artistic process, Kentridge stressed he works collaboratively and in a fragmented way. He created the text for his new productions through fragments from literary and historical texts, even classical Greek texts, which are then restructured and connected to create a cohesive work.

“I’m not a writer, I’m a collector. I make a montage of different found texts. I have a notebook where I record different things I’ve read,” he explained.

Kentridge confessed the fragmented nature of his theatrical and film productions is rooted in the fact that he considers himself a “useless storyteller”. When he tried in the past to write scripts in a linear way, he failed miserably, he said. “But if I say, here’s an image I want, I’m not sure where it fits in or what it means, but I’m confident about its relevance, it becomes a starting point. And from that, another idea is suggested.”

For The Great YES, the Great No Kentridge is working with a group of South African singers and performers who collaborate with composer Nhlanhla Mahlangu and director Tlale Makhene to translate the text into different South African languages such as Venda, Zulu, Xhosa and Swati. “The women in the chorus are also the composers, not simply performers of someone else’s composition,” Kentridge stressed.

“As we add fragments, we hope that cumulatively they don’t remain simply fragments, but their connections start to suggest themselves to us and hopefully, in the end to the audience watching it.” Collating fragments collaboratively, also with digital artists and designers, is a way of sparking new thinking and understanding, Kentridge remarked.

In an engrossing video clip of rehearsals of the The Great YES, The Great No, the audience was treated to a snapshot of Kentridge’s innovative take on a fraught history represented by different artists and thinkers. “Disaster has fallen on everyone, everywhere,” the chorus sings. “Why is this age worse than others? / Misfortune flows as from a water main.”

Bhabha pointed out the surrealist elements in The Great YES, The Great No are amplified by the voyage’s conflation with other forced sea crossings, historical and contemporary.

He suggested that Fanon’s idea of risk can be linked to Kentridge’s adaptation of surrealism. But unlike other surrealist artists, risk to Kentridge is less about chance and more concerned with existential threats.

“In my interpretation, what you’re saying is the universals are never fundamental principles alone. The big questions often become universal because we ask these questions again and again at different times. So, the universal is not a fundamental assumption, it’s an interrogation,” Bhabha noted.

He complimented Kentridge on how skilfully he framed universal questions. “What you’ve done so brilliantly, I think, is that you have emphasised the urgent banality of such questions.”

Although rooted in historical events, Kentridge’s work reverberates in the present, he added. “It seems to me the work is so relevant now, not simply because these questions are provocative, but because we’re always in the moment of both transition and translation as we make sense of the world around us.”

More than multiculturalism

Although surrealism was initially a French artistic movement, it became a tool of wider anti-colonial representation, Kentridge pointed out.

Bhabha referred to Fanon’s idea of a regional kind of nationalism rooted in a sense of internationalism. This concept is echoed in Kentridge’s ship of fools, prophets, poets and painters – people who borrowed and translated vocabularies from many cultures and places, Bhabha pointed out. “I think for our time, and for the moment of migrants and refugees now, despite the political injustices, there is a lesson to be learned about a certain kind of hybridised or vernacular cosmopolitanism, which this work brings out very clearly.

“This is not simply multiculturalism. It is a much more translational intersected sense of a cosmopolitan global movement. And that interests me very much, because I think this work really brings possibilities to life of finding new linkages, new connections, new solidarities,” Bhabha said.

He credited Kentridge with creating art that is inherently both retrospective and visionary. “This continuous activism of shifting meanings, translating and working with what is transitional is a great achievement.”

Responding to a question from the audience, Kentridge said although surrealism is a strategy that informs his work, he doesn’t consider The Great YES, the Great No a purely surrealist work. “In some ways it is, in other ways not. I don’t rely on chance in the same way as other surrealists. We don’t pull lines out of a hat. It’s nice to play with chance in a project like this, but once chance has had its say, we’re quite careful about it.”

Gobodo-Madikizela thanked the speakers for their insightful conversation. “As scholars and emerging scholars, we need these rich and deeply engaging conversation. It’s an honour for Stellenbosch University to host such generous and brilliant thinkers,” she said.