Re-encountering the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

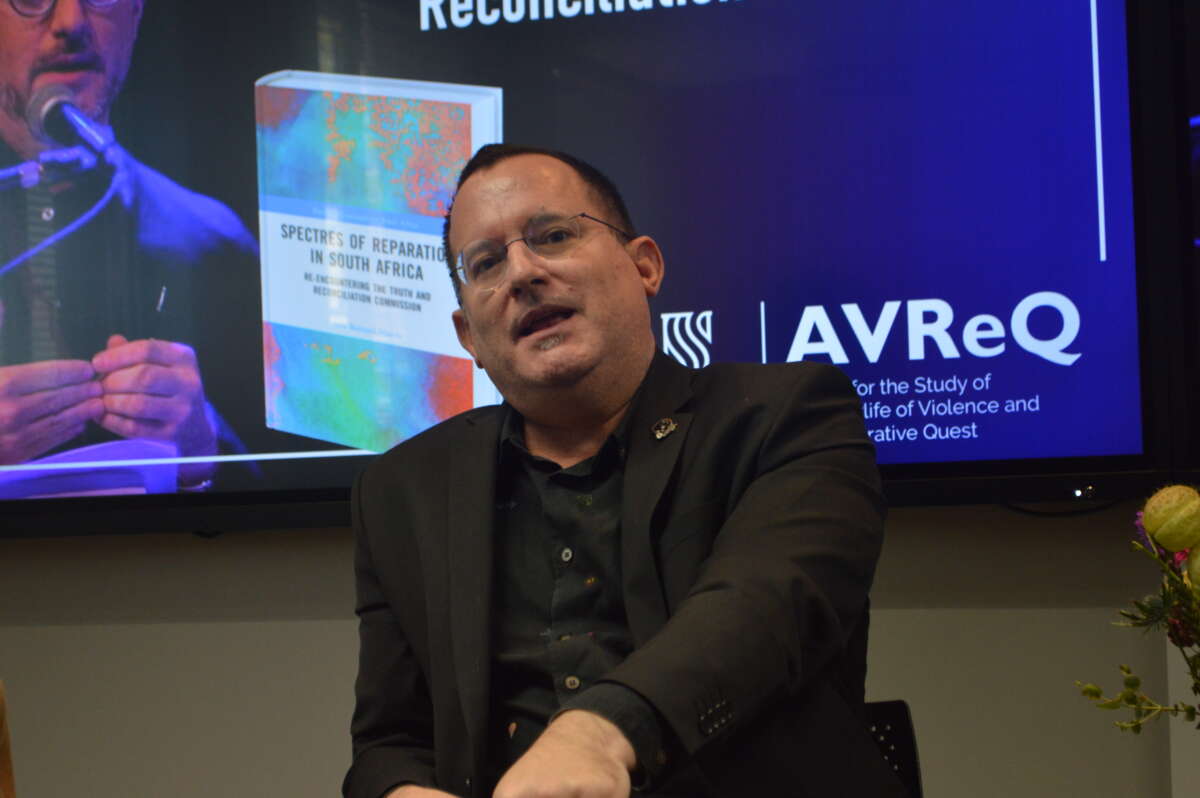

In a recent public lecture, Prof Jaco Barnard-Naudé delved into the heart of South Africa’s ongoing struggle with reparation. His discussion, deeply rooted in his book’s analysis, shed light on critical themes and arguments surrounding the South Africa’s post-apartheid challenges.

At the core of Prof Barnard-Naudé’s lecture was a moving quote by Joe Slovo, encapsulating the book’s essence: “without reparation, no law will stop the apartheid ghost from haunting our society.” This quote reverberates throughout the discussion, highlighting the profound impact of the lack of reparation on South Africa’s societal fabric.

One key aspect Barnard-Naudé addressed is the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a subject central to his analysis. He emphasized viewing the TRC not just as an institution but as a subject of lack, intricately intertwined with the country’s historical and constitutional complexities. The book meticulously dissects the TRC’s genesis from the 1993 interim constitution’s epilogue, framing South Africa’s national identity in terms of lack—specifically, the lack of understanding, reparation, and ubuntu (humanity). Barnard-Naudé argues that this lack, particularly the lack of reparation, permeates the TRC’s very structure and mandate.

For Barnard-Naudé, one critical observation from the book is the TRC’s limited powers regarding reparations. While it could recommend reparations to parliament, it lacked the authority to enforce them—an inherent deficiency that he highlights as a constitutive lack of the TRC itself. Throughout the discussion, Barnard-Naudé navigated various chapters of his book, addressing the biopolitical imperative of the TRC, its amnesty process, the role of the business sector during apartheid, and the intricate relationship between mourning, forgiveness, and reparation.

The book’s conclusion presents a compelling proposition: an ethic of reparative citizenship. This concept, as Barnard-Naudé articulates, offers a creative and productive way of engaging with the specter of reparation, acknowledging that while the specter may never be fully exorcised, meaningful encounters can lead to emancipatory possibilities. In essence, Prof Barnard-Naudé’s discussion and book provide a nuanced understanding of South Africa’s journey toward healing, justice, and reconciliation, offering a roadmap for navigating the complexities of post-apartheid society while confronting the ghosts of its past.

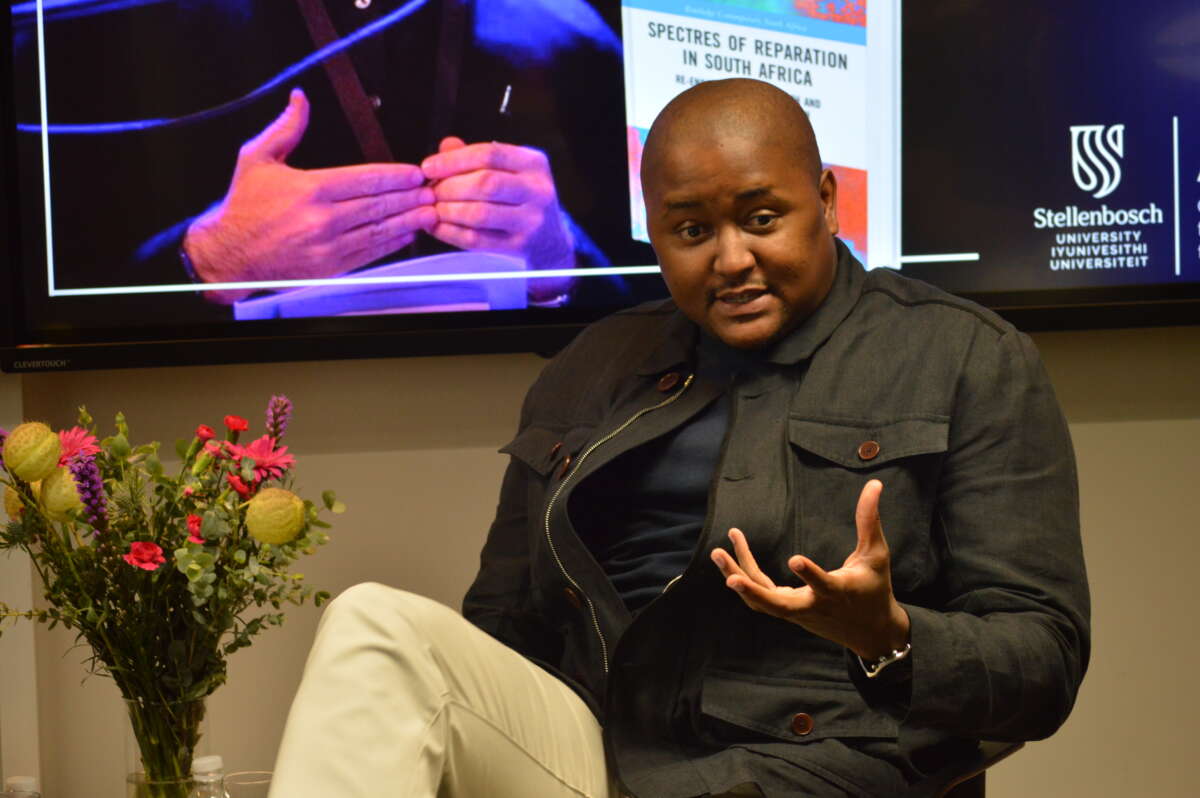

In his response Prof Joel Modiri, offered critical insights into the themes of reparation, memory, and insurgency. He begins by acknowledging the profound insights and provocations in Barnard-Naudé’s work, particularly highlighting the notions of psychoanalysis, transitional justice’s misadventures, and the use of Ubuntu in South African political discourse. However, Modiri narrows his discussion to three key prompts from the book that caught his attention.

The first prompt revolves around the TRC as a subject marked by lack, especially the lack of reparation. Modiri delves into the historical and constitutional underpinnings of South Africa, noting that both the historical formation and founding laws negate reparation due to the irreparable nature of the country’s history. He echoes Barnard-Naudé’s assertion that true reparations and decolonization might fundamentally alter South Africa’s identity, perhaps even signalling the end of its current state.

Modiri’s second prompt explored South Africa as a time-space characterized by the irreparable. He emphasizes the enduring impact of colonialism, racial domination, and anti-blackness on South African society, pointing out the structural violence and psychosocial traumas ingrained in its foundations. This prompts a critical reflection on hope, adequacy, and forms of optimism present in Barnard-Naudé’s work, expressing concerns about whether mere affirmation can adequately address the deep-rooted issues.

Lastly, Modiri discusses Barnard-Naudé’s turn to affirmation and the entanglement between reparation and decolonization. He questions whether this move risks falling into liberal optimism or if it can genuinely lead to transformative change. Modiri challenges the notion of narrating, redressing, or forgiving colonialism and apartheid, suggesting that these attempts may inadvertently reinforce the founding antagonisms rather than resolve them.

In considering alternatives to traditional transitional justice frameworks, Prof Modiri suggests the concept of reparative insurgency. This approach, reminiscent of figures like Sobukwe and Biko, calls into question the existing narratives and structures that perpetuate inequality and injustice. It challenges us to confront the uncomfortable truths of history and to seek transformative change that goes beyond mere affirmation or reconciliation without justice.

In conclusion, the dialogue between Prof Modiri’s insights and Prof Barnard-Naudé’s work prompts a deeper reflection on the complexities of transitional justice in South Africa. It invites us to rethink conventional approaches and consider new possibilities for addressing historical injustices and building a more equitable and just society. The path towards true reconciliation and healing requires a nuanced understanding of irreparability, a willingness to confront uncomfortable truths, and a commitment to transformative action.