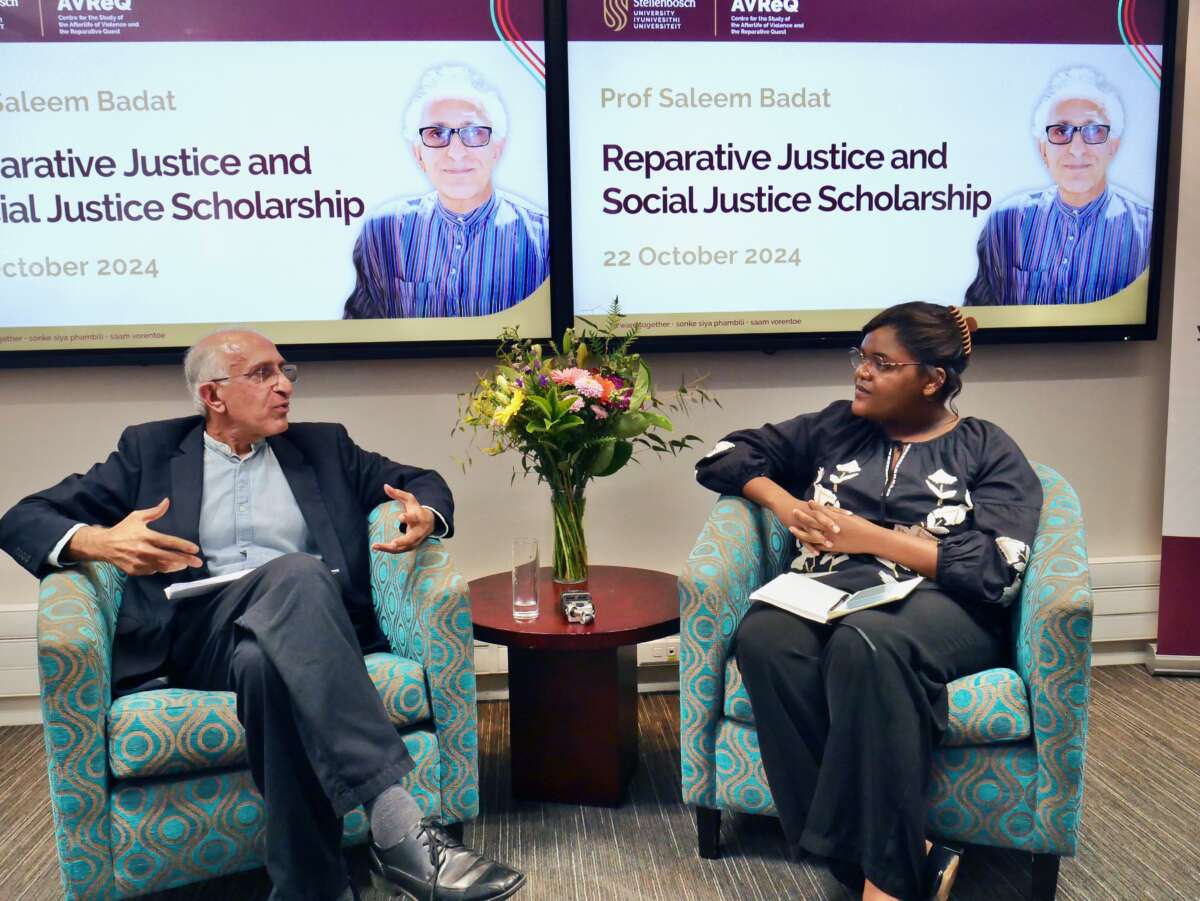

Prof Saleem Badat, a research professor from the University of the Free State, delivered a compelling lecture on the urgent need for reparative justice in South Africa. Hosted by AVReQ and moderated by Dr Anell Daries, the seminar explored both Prof Badat’s personal experiences and broader historical injustices. Through a series of vignettes, Badat illuminated the lasting impact of apartheid and the role of reparative justice in achieving meaningful social transformation. Prof Badat underscored that reparative justice goes beyond symbolic gestures, emphasizing that “reparative justice is not about money alone but about repairing the structural and relational harm that persists in society.” He also challenged the notion of post-apartheid “inclusion,” stressing that inclusion without structural transformation often masks the realities of enduring inequality. “Inclusion is not the same as diversity, and neither implies equity. We need to question and redefine what inclusion truly means in a South African context,” Badat argued.

Badat framed his lecture around four personal and historical experiences. The first centred on his own experience of detention and torture under apartheid. Awarded a reparative sum of R30,000 through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Badat said the amount offered minimal consolation and instead prompted him to question what real reparative justice might look like. His second vignette examined the role of universities under apartheid and how they continue to embody colonial structures. Badat noted that “our universities, even today, still largely reflect the architecture of colonial intellectual thought and exclusion.” He urged academic institutions to undergo meaningful transformations, advocating for reparative programs that extend beyond offering a few scholarships to historically disadvantaged students.

In the third vignette, he spoke about the legacy of apartheid-era banishment, referencing his book The Forgotten People, which details the displacement of rural African leaders. This story, he suggested, highlights the state’s ongoing failure to memorialise and compensate those who suffered banishment. As Prof Badat told the audience, “these lives and histories are absent from our national consciousness. Reparative justice would demand that we remember and honour them properly.” The fourth vignette addressed the exclusion of Black South African tennis players, particularly Hussein Boubert, from competing in Wimbledon in 1971. Badat’s recent book, Tennis, Apartheid & Social Justice, calls for an apology from Wimbledon and the International Tennis Federation for barring Boubert due to apartheid policies. Despite advocacy efforts, the request remains unmet, a fact he said exemplifies “the discomfort elites have in acknowledging and apologizing for their complicity in exclusionary practices.”

Reparative Justice and Its Scope

In conversation with Dr Daries, Badat highlighted the limitations of reparations framed only around individual cases of torture and detention, as seen in the TRC model. He pointed out that true reparative justice must extend to communities impacted by systemic exclusions, such as forced removals and under-resourced health and education systems. “If we want reparative justice that makes a difference, we have to tackle the very structures of inequality,” he insisted. The discussion then turned to the institutional inertia that often hampers efforts at reparative justice, with Dr Daries referencing the challenges her division faces in gaining university support for such initiatives. Badat emphasized that universities must be held accountable to their communities, calling for a long-term investment in partnership and restorative initiatives rather than “individual historical rectification.” “This work is not about ticking a box,” he said, “it’s about making deep, long-term commitments that build generational change.”

The Role of Scholars in Advancing Social Justice

Addressing the academic audience, Badat urged scholars to take their social responsibility seriously, questioning whether academia is genuinely committed to social impact. “After your article is written, after your book is published—what’s next? Reparative justice doesn’t end with publication,” he said. He called on universities and scholars to engage directly with the communities affected by their research, challenging what he termed “a culture of isolated scholarship.” Dr Daries echoed this sentiment, emphasizing that impactful research should not be treated as an add-on but as an integral part of academic work. Badat warned against “academics using reparative justice as a CV exercise,” highlighting the importance of authentic engagement.

Revisiting Apartheid’s Legacy and Mandela’s Role

Reflecting on Mandela’s efforts during the transition to democracy, Badat offered a nuanced perspective, cautioning against the overly simplistic narrative that paints Mandela as a “sellout.” He acknowledged Mandela’s compromises as necessary for averting civil war but suggested that these compromises created challenges for the realisation of deep-seated justice in the post-apartheid era. “1994 marked the start of a new struggle, a struggle to make freedom mean something real for every South African,” Badat remarked.

The dialogue between Badat and Daries ultimately underlined the urgent need for South Africans to engage in difficult but necessary conversations about the country’s past and the path forward. From universities to sports federations, Badat argued, all institutions must be willing to acknowledge their role in upholding systems of exclusion and actively work toward redress. As the event concluded, Badat left the audience with a powerful reminder: reparative justice, at its core, is not about symbolic gestures. “It’s about real transformation, about addressing the legacies of harm, and, crucially, preventing them from being reproduced.”